Advanced Search

Pitcher

Newell Harding (1796–1862)

about 1851

Object Place: Boston, Massachusetts, United States

Medium/Technique

Silver

Dimensions

18.5 x 19.2 x 14 cm (7 5/16 x 7 9/16 x 5 1/2 in.)

Credit Line

Charles T. and Susan P. Baker by bequest of the latter

Accession Number21.1258

NOT ON VIEW

CollectionsAmericas

ClassificationsSilver hollowware

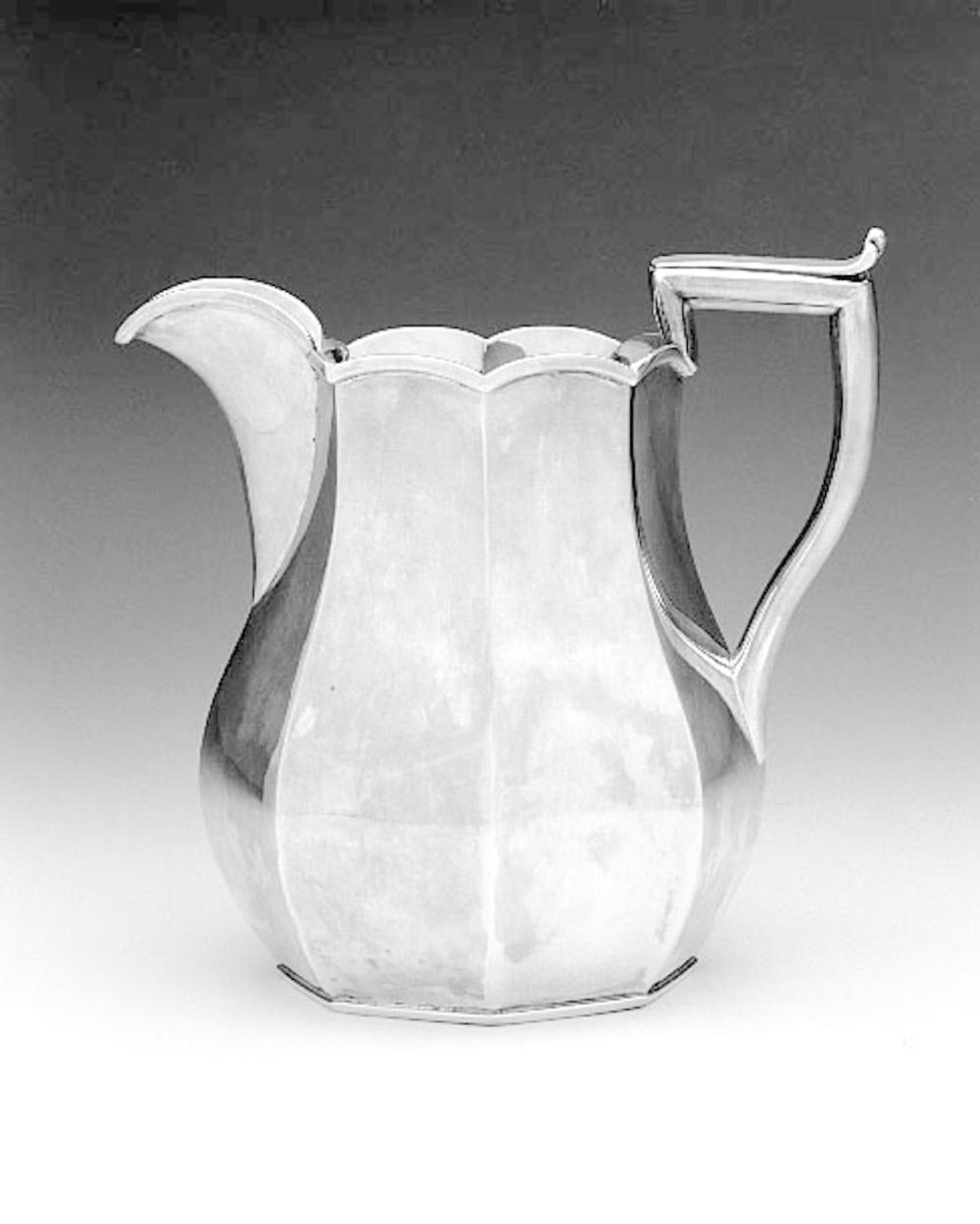

In this small but gracefully proportioned paneled pitcher, the plain, highly polished surfaces combine with the octagonal form to reflect light and create dramatic shadows. Newell Harding’s reputation was based on the manufacture of flatware, and it is unclear whether the firm manufactured or only purchased solid silver hollowware for retail. Although marked with Harding’s pre-1851 mark, this pitcher may have been produced by another silversmith and purchased for retail sale by Harding.

Harding was the son of Jesse and Hannah (Webster) Harding of Haverhill, Massachusetts. It has long been maintained that he apprenticed in Boston with Hazen Morse (1790 – 1874), the Haverhill-born silversmith and engraver. Thirty years after his death, Harding was hailed in the Annals of the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanics Association as “probably the best known silversmith in New England in his day.” He joined the association early in his career, in 1828, and in 1837 received a silver medal in its first exhibition, honored for “A case of Silver Table Ware, comprising spoons, forks, ladles, sugar tongs, fish and butter knives . . . 94 pieces all made in a finished, superior, massy manner.” He actively maintained his membership throughout his life and acted as a silverware judge at the 1848 and later exhibitions.

Harding commenced business shortly before Boston incorporated in 1822; the city’s population had more than doubled since 1800, to approximately 57,000. Ambitious and graced with an entrepreneurial outlook, Harding flourished, and his firm continued in the Court Square area of upper Washington Street until 1889. Much of the information published to date about the firm has been drawn from the 1856 publication Leading Men and Leading Pursuits, produced to showcase the principal trades and industries of the United States. The publication reported that early in his career, Harding confined his business to spoonmaking, a practice seen as innovative since most silversmiths in the 1820s produced a variety of flatware and hollowware. His spoon business was described as so successful that “Newell Harding became a household word in New England.” The publication further credited him with being the first in Boston to introduce power for the purpose of rolling silver; to segment the operation to increase production and allow for “more highly finished work”; and to introduce the “ornamental style of work now so much in vogue.” The report claimed Newell Harding & Co., which had thirty-five workers, employed the “only silversmiths in Boston who make and sell their own work to consumers.” A large ad within lists more than fifty available flatware forms but mentions no hollowware. The firm did, however, advertise both flatware and hollowware in an ad in the Boston directory of 1857.

In 1851 Harding, in business since 1821, entered into a partnership with his eldest son, Francis Low Harding (1806 – 1906), as well as Alexander H. Lewis (1815 – 1859) and Lewis A. Kimball (w. about 1851 – 85), to form Newell Harding & Co. According to contemporary R. G. Dun credit reports, Harding leased the land at 12 Court Street but owned the shop and store at that address. Known in 1852 as good mechanics with a solid retail business, they were considered safe credit risks. Two years later, Dun reported that the firm was known to “manufacture considerably for the dealers . . . though possibly not so much as before . . . and was known to seek family patronage.”

By 1860 large manufacturers such as Gorham had begun to dominate the industry, whereas small and medium-sized firms struggled to remain competitive. Internal problems beset Harding’s firm as well. R. G. Dun reported that the “young Hardings habits [were] considered rather free” after the death of the remaining “substantial” member, partner Alexander H. Lewis, in 1859. Subsequently, caution was advised in dealing with the firm. It was noted that Francis Low Harding withdrew from the partnership and that the senior Harding was “drinking badly” when the firm’s 12 Court Street land lease was not renewed in 1861. After Newell Harding Sr. died in 1862, the firm continued under his name, operated by Lewis Kimball and Harding’s remaining sons.

During the 1860s, in an effort to take advantage of the market for less expensive plated wares, Harding & Co., like many other retailers, operated their own plating department and purchased goods “in the metal” (unplated) from Reed & Barton in Taunton, Massachusetts. Newell Harding Jr., who had separated from the family business for a few years after his father’s death (apparently with feelings of ill will), maintained a separate listing in the Boston directory for several years; however, by 1868 he had rejoined the firm. In 1875 Julius L. D. Sullivan (born in 1833 in Cambridge, Massachusetts) is listed together with the reunited brothers, Francis Low Harding (1826 – 1906), Webb Harding (about 1832 – after 1875), and Newell Harding Jr. (1834 – 1885), as Newell Harding & Co. Although it is unclear how the business was divided between retailing and manufacturing, the firm continued for another twenty years at Court Street, School Street, or Washington Street addresses, disappearing from the Boston directory in 1890.

This text has been adapted from "Silver of the Americas, 1600-2000," edited by Jeannine Falino and Gerald W.R. Ward, published in 2008 by the MFA. Complete references can be found in that publication.

Harding was the son of Jesse and Hannah (Webster) Harding of Haverhill, Massachusetts. It has long been maintained that he apprenticed in Boston with Hazen Morse (1790 – 1874), the Haverhill-born silversmith and engraver. Thirty years after his death, Harding was hailed in the Annals of the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanics Association as “probably the best known silversmith in New England in his day.” He joined the association early in his career, in 1828, and in 1837 received a silver medal in its first exhibition, honored for “A case of Silver Table Ware, comprising spoons, forks, ladles, sugar tongs, fish and butter knives . . . 94 pieces all made in a finished, superior, massy manner.” He actively maintained his membership throughout his life and acted as a silverware judge at the 1848 and later exhibitions.

Harding commenced business shortly before Boston incorporated in 1822; the city’s population had more than doubled since 1800, to approximately 57,000. Ambitious and graced with an entrepreneurial outlook, Harding flourished, and his firm continued in the Court Square area of upper Washington Street until 1889. Much of the information published to date about the firm has been drawn from the 1856 publication Leading Men and Leading Pursuits, produced to showcase the principal trades and industries of the United States. The publication reported that early in his career, Harding confined his business to spoonmaking, a practice seen as innovative since most silversmiths in the 1820s produced a variety of flatware and hollowware. His spoon business was described as so successful that “Newell Harding became a household word in New England.” The publication further credited him with being the first in Boston to introduce power for the purpose of rolling silver; to segment the operation to increase production and allow for “more highly finished work”; and to introduce the “ornamental style of work now so much in vogue.” The report claimed Newell Harding & Co., which had thirty-five workers, employed the “only silversmiths in Boston who make and sell their own work to consumers.” A large ad within lists more than fifty available flatware forms but mentions no hollowware. The firm did, however, advertise both flatware and hollowware in an ad in the Boston directory of 1857.

In 1851 Harding, in business since 1821, entered into a partnership with his eldest son, Francis Low Harding (1806 – 1906), as well as Alexander H. Lewis (1815 – 1859) and Lewis A. Kimball (w. about 1851 – 85), to form Newell Harding & Co. According to contemporary R. G. Dun credit reports, Harding leased the land at 12 Court Street but owned the shop and store at that address. Known in 1852 as good mechanics with a solid retail business, they were considered safe credit risks. Two years later, Dun reported that the firm was known to “manufacture considerably for the dealers . . . though possibly not so much as before . . . and was known to seek family patronage.”

By 1860 large manufacturers such as Gorham had begun to dominate the industry, whereas small and medium-sized firms struggled to remain competitive. Internal problems beset Harding’s firm as well. R. G. Dun reported that the “young Hardings habits [were] considered rather free” after the death of the remaining “substantial” member, partner Alexander H. Lewis, in 1859. Subsequently, caution was advised in dealing with the firm. It was noted that Francis Low Harding withdrew from the partnership and that the senior Harding was “drinking badly” when the firm’s 12 Court Street land lease was not renewed in 1861. After Newell Harding Sr. died in 1862, the firm continued under his name, operated by Lewis Kimball and Harding’s remaining sons.

During the 1860s, in an effort to take advantage of the market for less expensive plated wares, Harding & Co., like many other retailers, operated their own plating department and purchased goods “in the metal” (unplated) from Reed & Barton in Taunton, Massachusetts. Newell Harding Jr., who had separated from the family business for a few years after his father’s death (apparently with feelings of ill will), maintained a separate listing in the Boston directory for several years; however, by 1868 he had rejoined the firm. In 1875 Julius L. D. Sullivan (born in 1833 in Cambridge, Massachusetts) is listed together with the reunited brothers, Francis Low Harding (1826 – 1906), Webb Harding (about 1832 – after 1875), and Newell Harding Jr. (1834 – 1885), as Newell Harding & Co. Although it is unclear how the business was divided between retailing and manufacturing, the firm continued for another twenty years at Court Street, School Street, or Washington Street addresses, disappearing from the Boston directory in 1890.

This text has been adapted from "Silver of the Americas, 1600-2000," edited by Jeannine Falino and Gerald W.R. Ward, published in 2008 by the MFA. Complete references can be found in that publication.

DescriptionThe vessel is octagonal in cross-section, its raised tulip-shaped body is faceted with eight panels. The scalloped rim, with an applied rounded edge, gives way to a large set-in spout that rises above the rim in a great curve complementing that of the lower body. The contrasting angular handle attaches to the rim; rises sharply; and curves down to the hip of the body, where its W-shaped bottom edge attaches near a small vent hole. The applied base is octagonal, and the center of the bottom is closed with a thinner circle of silver. An applied edge on the base conforms to that surrounding the upper rim.

Marks

Stamped "N. Harding" in script within a banner and "Pure Silver Coin" in a rectangle; "BOSTON" struck incuse in uppercase Roman letters .

Ada Mark * F4735

Ada Mark * F4735

InscriptionsEngraved "Susan P. Baker" in script on the top surface of the applied thumbpiece.

ProvenanceCharles Tidd Baker (1830-1905) and Susan Porter Baker (1837-1921) are the donors of other items in the collection (see 21.1261).The sauceboats were probably made for Henry Porter (b. 1793) of Medford, and his wife Susan Simpson Tidd (1803-1853) of Boston, sometime after their marriage in 1824. Charles Tidd Porter (1825-26), their first-born son, died as an infant, and it is possible that one or two additional children, named Susan Emily Porter (bp. 1828) and Francis Henry Porter (bp. 1833), also died young. The donors of the sauceboats were siblings on the Tidd side of the family whose birthdates postdate those of their Porter cousins. Susan Porter Baker (1837-1921) and Charles Tidd Baker (1830-1905), were the namesakes and first cousins of the first two Porter children, and likely recipients of the family silver.

Two additional items given by the donors, a Zachariah Brigden porringer (Buhler 1972 1:375, cat. 329) and a David Mosely cann (Buhler 1972 2:504, cat. 451), each bearing the initials "T / I R," indicate ownership in the Tidd family.

Sources:

Henry S. Nourse, ed., The Birth, Marriage, and Death Register, Church Records and Epitaphs of Lancaster, Massachusetts, 1643-1850 (Lancaster, Ma., 1890), P. 176,362; 237; Obituaries, Boston Globe 20 (1905):210; 1 (1921)336; Vital Records of Medford to the Year 1850 (Boston: New England Historical Genealogical Society, 1907), pp. 277, 305, 113, 417; Thomas W. Baldwin, comp., Vital Records of Cambridge, Massachusetts to the Year 1850), (Boston, ,1914); I:33, II. 458; death certificates, Massachusetts Vital Records.

Two additional items given by the donors, a Zachariah Brigden porringer (Buhler 1972 1:375, cat. 329) and a David Mosely cann (Buhler 1972 2:504, cat. 451), each bearing the initials "T / I R," indicate ownership in the Tidd family.

Sources:

Henry S. Nourse, ed., The Birth, Marriage, and Death Register, Church Records and Epitaphs of Lancaster, Massachusetts, 1643-1850 (Lancaster, Ma., 1890), P. 176,362; 237; Obituaries, Boston Globe 20 (1905):210; 1 (1921)336; Vital Records of Medford to the Year 1850 (Boston: New England Historical Genealogical Society, 1907), pp. 277, 305, 113, 417; Thomas W. Baldwin, comp., Vital Records of Cambridge, Massachusetts to the Year 1850), (Boston, ,1914); I:33, II. 458; death certificates, Massachusetts Vital Records.