Advanced Search

Paul Revere

John Singleton Copley (American, 1738–1815)

1768

Medium/Technique

Oil on canvas

Dimensions

89.22 x 72.39 cm (35 1/8 x 28 1/2 in.)

Credit Line

Gift of Joseph W. Revere, William B. Revere and Edward H. R. Revere

Accession Number30.781

CollectionsAmericas

ClassificationsPaintings

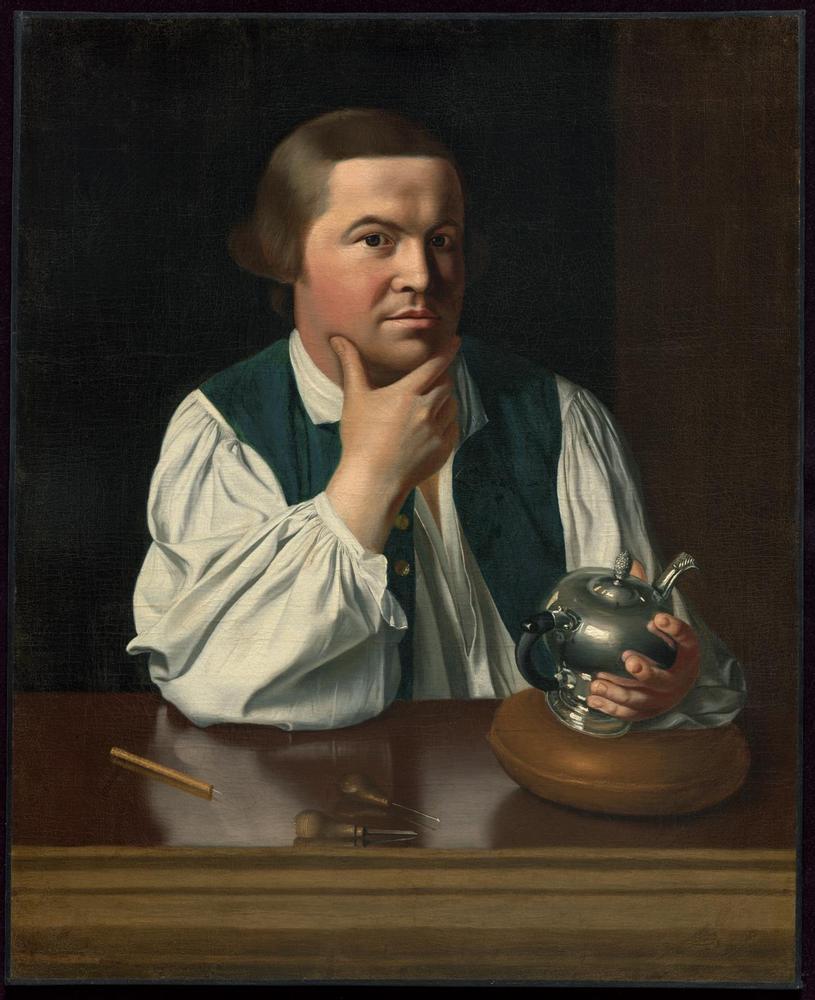

Paul Revere is Copley’s only finished portrait of an artisan dressed in shirtsleeves and shown at work. Revere is shown half-length, seated behind a highly polished table, and casually attired. He cradles his chin in his right hand and regards the viewer as if he has just looked up from the teapot in his left hand; the pot is finished but remains undecorated, and the engraving tools at Revere’s elbow attest to the work yet to come. When Copley painted Revere’s portrait, his sitter was an accomplished, well-established silversmith and master of the rococo style, both in engraving and in three-dimensional hollowware such as teapots [35.1775]. He completed the Sons of Liberty Bowl [49.45], now considered one of the United States’ most cherished historical treasures, the same year Copley captured his likeness.

Copley’s image of Revere is unprecedented not only in his own oeuvre but also in American colonial painting. Though Copley had produced a few portraits of craftsmen, his usual patrons were clergymen and merchants and their wives. He first depicted an artisan with the attributes of his trade in one of his earliest portraits, Peter Pelham (?) (private collection), dated about 1754. Like Revere, the subject is seated at a table strewn with tools, but this craftsman wears a jacket, stock, and patterned waistcoat. The more formal attire makes the sitter appear posed rather than caught in the middle of his work. Peter Pelham (?) bears striking similarities to the mezzotint John TheophilusDesaguliers [M20149] by Copley’s stepfather, Peter Pelham. [1]Copley may have referred to Pelham’s mezzotint and also to his own Peter Pelham (?) for the composition, pose, and other details of Paul Revere. Both mezzotint and early portrait, like Paul Revere, offer half-length views of figures seated behind tables with tools; each of these subjects, like Revere, is turned slightly to the side, right arm leaning on a table, left hand holding an object—a magnifying glass in the case of Desaguliers and an engraving tool and burin in the case of the sitter presumed to be Pelham—and each man looks straight out at the viewer. The print is closer to Paul Revere in some respects, however. The table in the mezzotint, like Revere’s table, is aligned parallel to the picture plane and not at a slightly awkward angle as in Peter Pelham (?); the complicated gathers of Revere’s sleeve seem to be derived directly from those of Desaguliers’s sleeve; and both Desaguliers’s magnifying glass and Revere’s teapot complement the sitters’ faces and reflect light. In conceiving of Paul Revere, Copley may also have been inspired by the European tradition of depicting artists and craftsmen with their tools and the objects they create as attributes or by Northern Renaissance portrayals of jewelers, goldsmiths, and bankers, images he would have known through prints.

The wigless Revere wears a plain white linen shirt with no cravat and only a hint of a frill on the right sleeve. The shirt is open, revealing an undershirt or possibly an untied stock beneath. His blue-green waistcoat, made of wool or matte silk, is likewise unfastened; two gold buttons are visible below Revere’s right hand. The open shirt and the waistcoat worn without a jacket are associated with work clothes. However, other aspects of his costume, such as its cleanliness and the gold buttons (possibly used here, along with the teapot, to advertise Revere’s products), do not accurately reflect the garments Revere actually wore to ply his trade. Moreover, the polished table is not the craftsman’s workbench. Thus, in his portrait of Revere, Copley presented an idealized image of the artisan at work.

Though Paul Revere is now one of the most celebrated of American portraits, the circumstances of its execution are uncertain. It is known that Copley had met Revere by 1763, when the painter ordered a gold bracelet from the smith, and it is recorded in Revere’s account book (The Revere Waste and Memoranda Book, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston) that Copley purchased frames and cases for his miniatures between 1763 and 1767. However, the occasion for the commission of this portrait and the identification of the client who paid for it remain mysteries. The date inscribed on the painting—1768—enhances the iconographic significance of the teapot, both as an aesthetic and a political symbol. Teapots were among the most complex objects Revere made; they represented his craft in its highest form. According to Revere’s account book, he made a total of nine teapots from 1762 to 1773. Of those nine, six were made between 1762 and 1765, one in 1768, and the other two in 1773. Revere’s production of teapots had declined by 1768 in response to the Townshend Acts, which imposed duties on a variety of imported goods including tea. The teapot, then, was a provocative attribute for Revere, especially given his radical Whig politics.

Unlike Copley’s portraits of Samuel Adams [L-R 30.76c] and John Hancock [L-R 30.76d], which were displayed in Faneuil Hall, Boston, and were translated into prints, Paul Revere did not become a public image during the Revolution or in its aftermath. The Copley portrait remained in the Revere family after the sitter’s death in 1818, apparently relegated to an attic. According to family tradition, Revere’s daughter Harriet so disliked the informality of the portrait that she had her nephew, Frederick Ballestier Revere, an amateur artist, make a copy using only the face from the original; he replaced the shirtsleeves with a red uniform and a gorget of crossed cannon, a testament to Paul Revere’s military service (Morristown National Historical Park, New Jersey).

The Revere family’s interest in the Copley portrait seems to have revived at about the time Henry Wadsworth Longfellow published his poem “Paul Revere’s Ride” in 1861, for it was reported that the painting had been restored by 1875. The portrait was not publicly displayed until 1928, when it was first loaned to the MFA; Revere’s great-grandsons gave the painting to the Museum in 1930. The current popularity of the portrait seems to have begun with the publication of Esther Forbes’s 1942 Pulitzer Prize–winning biography of Paul Revere, which used the Copley portrait as the frontispiece. [2]

Notes

1. See Trevor J. Fairbrother, “John Singleton Copley’s Use of British Mezzotints for his American Portraits: A Reappraisal Prompted by New Discoveries,”Arts Magazine 55 (March 1981): 122–30.

2. Esther Forbes, Paul Revere and the World He Lived In (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1948).

This text was adapted and expanded by Karen E. Quinn from her own entry in John Singleton Copley in America, by Carrie Rebora et al., exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art in association with Harry N. Abrams, 1995).

Copley’s image of Revere is unprecedented not only in his own oeuvre but also in American colonial painting. Though Copley had produced a few portraits of craftsmen, his usual patrons were clergymen and merchants and their wives. He first depicted an artisan with the attributes of his trade in one of his earliest portraits, Peter Pelham (?) (private collection), dated about 1754. Like Revere, the subject is seated at a table strewn with tools, but this craftsman wears a jacket, stock, and patterned waistcoat. The more formal attire makes the sitter appear posed rather than caught in the middle of his work. Peter Pelham (?) bears striking similarities to the mezzotint John TheophilusDesaguliers [M20149] by Copley’s stepfather, Peter Pelham. [1]Copley may have referred to Pelham’s mezzotint and also to his own Peter Pelham (?) for the composition, pose, and other details of Paul Revere. Both mezzotint and early portrait, like Paul Revere, offer half-length views of figures seated behind tables with tools; each of these subjects, like Revere, is turned slightly to the side, right arm leaning on a table, left hand holding an object—a magnifying glass in the case of Desaguliers and an engraving tool and burin in the case of the sitter presumed to be Pelham—and each man looks straight out at the viewer. The print is closer to Paul Revere in some respects, however. The table in the mezzotint, like Revere’s table, is aligned parallel to the picture plane and not at a slightly awkward angle as in Peter Pelham (?); the complicated gathers of Revere’s sleeve seem to be derived directly from those of Desaguliers’s sleeve; and both Desaguliers’s magnifying glass and Revere’s teapot complement the sitters’ faces and reflect light. In conceiving of Paul Revere, Copley may also have been inspired by the European tradition of depicting artists and craftsmen with their tools and the objects they create as attributes or by Northern Renaissance portrayals of jewelers, goldsmiths, and bankers, images he would have known through prints.

The wigless Revere wears a plain white linen shirt with no cravat and only a hint of a frill on the right sleeve. The shirt is open, revealing an undershirt or possibly an untied stock beneath. His blue-green waistcoat, made of wool or matte silk, is likewise unfastened; two gold buttons are visible below Revere’s right hand. The open shirt and the waistcoat worn without a jacket are associated with work clothes. However, other aspects of his costume, such as its cleanliness and the gold buttons (possibly used here, along with the teapot, to advertise Revere’s products), do not accurately reflect the garments Revere actually wore to ply his trade. Moreover, the polished table is not the craftsman’s workbench. Thus, in his portrait of Revere, Copley presented an idealized image of the artisan at work.

Though Paul Revere is now one of the most celebrated of American portraits, the circumstances of its execution are uncertain. It is known that Copley had met Revere by 1763, when the painter ordered a gold bracelet from the smith, and it is recorded in Revere’s account book (The Revere Waste and Memoranda Book, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston) that Copley purchased frames and cases for his miniatures between 1763 and 1767. However, the occasion for the commission of this portrait and the identification of the client who paid for it remain mysteries. The date inscribed on the painting—1768—enhances the iconographic significance of the teapot, both as an aesthetic and a political symbol. Teapots were among the most complex objects Revere made; they represented his craft in its highest form. According to Revere’s account book, he made a total of nine teapots from 1762 to 1773. Of those nine, six were made between 1762 and 1765, one in 1768, and the other two in 1773. Revere’s production of teapots had declined by 1768 in response to the Townshend Acts, which imposed duties on a variety of imported goods including tea. The teapot, then, was a provocative attribute for Revere, especially given his radical Whig politics.

Unlike Copley’s portraits of Samuel Adams [L-R 30.76c] and John Hancock [L-R 30.76d], which were displayed in Faneuil Hall, Boston, and were translated into prints, Paul Revere did not become a public image during the Revolution or in its aftermath. The Copley portrait remained in the Revere family after the sitter’s death in 1818, apparently relegated to an attic. According to family tradition, Revere’s daughter Harriet so disliked the informality of the portrait that she had her nephew, Frederick Ballestier Revere, an amateur artist, make a copy using only the face from the original; he replaced the shirtsleeves with a red uniform and a gorget of crossed cannon, a testament to Paul Revere’s military service (Morristown National Historical Park, New Jersey).

The Revere family’s interest in the Copley portrait seems to have revived at about the time Henry Wadsworth Longfellow published his poem “Paul Revere’s Ride” in 1861, for it was reported that the painting had been restored by 1875. The portrait was not publicly displayed until 1928, when it was first loaned to the MFA; Revere’s great-grandsons gave the painting to the Museum in 1930. The current popularity of the portrait seems to have begun with the publication of Esther Forbes’s 1942 Pulitzer Prize–winning biography of Paul Revere, which used the Copley portrait as the frontispiece. [2]

Notes

1. See Trevor J. Fairbrother, “John Singleton Copley’s Use of British Mezzotints for his American Portraits: A Reappraisal Prompted by New Discoveries,”Arts Magazine 55 (March 1981): 122–30.

2. Esther Forbes, Paul Revere and the World He Lived In (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1948).

This text was adapted and expanded by Karen E. Quinn from her own entry in John Singleton Copley in America, by Carrie Rebora et al., exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art in association with Harry N. Abrams, 1995).

InscriptionsLower right: 1768

ProvenanceBy 1873, descended in the Revere family to the sitter's grandson, John Revere (1822-1886), Boston; 1886, by descent to his wife, Susan Tilden Torrey Revere (Mrs. John Revere, 1826-1911), Canton, Mass.; 1911, by descent to her sons, Joseph Warren Revere (1848-1932), Canton, Mass., William Bacon Revere (1859-1948), Canton, Mass., and Edward Hutchinson Robbins Revere (1867-1957), Canton, Mass.; 1930, gift of Joseph W. Revere, William B. Revere and Edward H. R. Revere to the MFA. (Accession Date: December 4, 1930)

ENG_305.mp3