Advanced Search

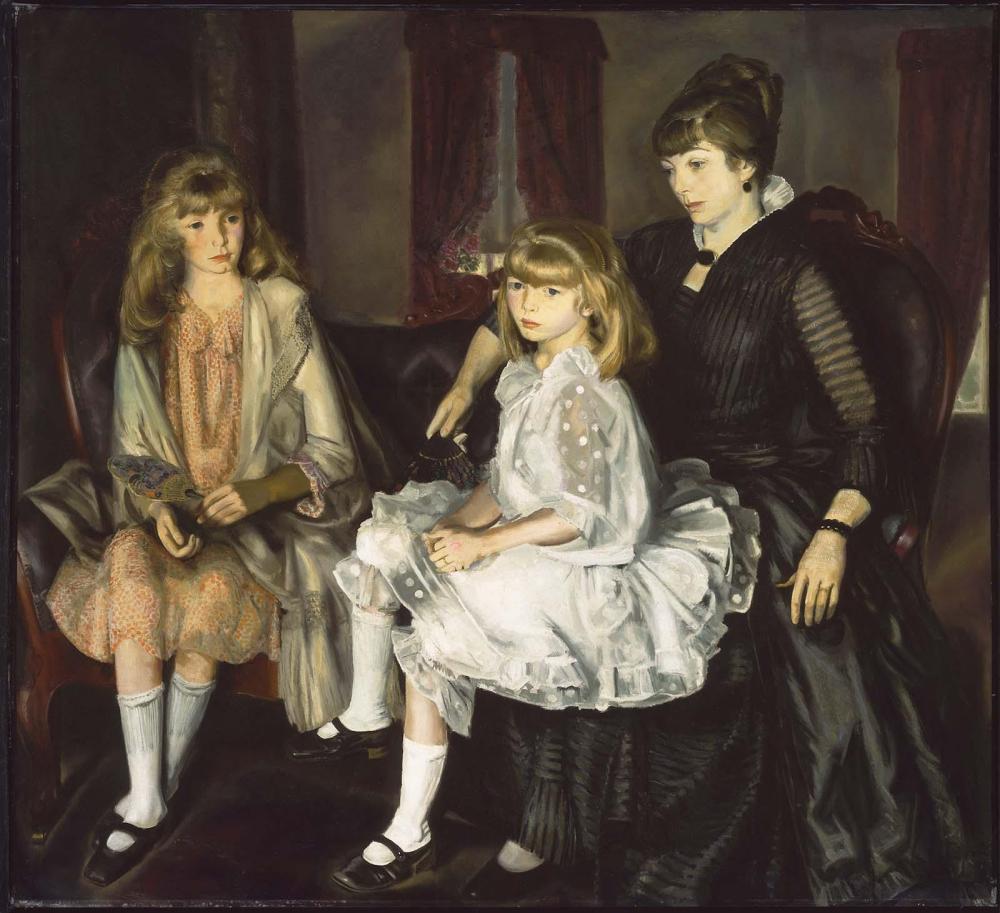

Emma and Her Children

George Wesley Bellows (American, 1882–1925)

1923

Medium/Technique

Oil on canvas

Dimensions

150.49 x 166.05 cm (59 1/4 x 65 3/8 in.)

Credit Line

Gift of subscribers and by purchase from the John Lowell Gardner Fund

Accession Number25.105

NOT ON VIEW

CollectionsAmericas

ClassificationsPaintings

Although he did not exhibit with the Manhattan painters called the Eight, who showed their works together at the Macbeth Gallery, George Bellows shared their realist philosophy, ideals that had earned them the nickname “the Ashcan School.” Like them, Bellows concentrated on urban New York themes, and he painted the excavations for Pennsylvania Station, the underworld of prizefighting contests, and tenement life on the Lower East Side. Closely associated with the many of the group’s leading figures, Bellows began his formal training with Robert Henri [http://www.mfa.org/search/collections?artist=Robert%20Earle%20Henri] at the New York School of Art in 1904 and also collaborated with John Sloan [35.52] as an illustrator for the socialist magazine the Masses between 1913 and 1917.

Emma and Her Children was painted towards the end of Bellows’s career during a productive summer he spent in Woodstock, New York, a favored art community in the Hudson River valley. The composition recalls Auguste Renoir’s large portrait of Madame Charpentier and her children (1878), which had entered the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, to great acclaim in 1907. Bellows posed his wife, Emma, and their two daughters in an elaborately conceived arrangement that evokes bourgeois respectability. In contrast to the seemingly unruffled world of Renoir, the Bellows portrait betrays anxiety. Emma recalled the tension of their portrait sittings in a letter of 1943. Although Bellows’s portrayal of her and their younger daughter Jean went very well “from the start,” she noted that it was more difficult to incorporate their twelve-year-old daughter Anne. [1] With maternal protectiveness, Emma’s arm encircles Jean, who sits unabashedly with legs askew surrounded by billowing crinolines. In contrast, Anne, on the cusp of maturity, exhibits a distinct nervousness in the pose of her hands and a sense of adolescent self-consciousness in her stiffly crossed ankles.

In a 1923 letter to Robert Henri, Bellows described technical innovations he had developed that afforded him the same freedom while painting that he experienced in drawing. By laying out the composition in two colors at the outset, as seen in the purple and orange that dominate the study [63.261] for this portrait, Bellows achieved “the fresh first excitement” of the composition. [2] Seeking to emulate the spontaneity of Renoir and the French Impressionists and his teacher Henri, Bellows hoped to establish the essential idea of the composition in one day of painting.

Notes

1. Emma Bellows to Barbara N. Parker, May 28, 1943, curatorial files, Department of Art of the Americas, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

2. George Bellows to Robert Henri, November 1923, quoted in Michael Quick et al., The Paintings of George Bellows, exh. cat. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1992), 84.

This text was adapted from Elliot Bostwick Davis et al., American Painting [http://www.mfashop.com/9020398034.html], MFA Highlights (Boston: MFA Publications, 2003).

Emma and Her Children was painted towards the end of Bellows’s career during a productive summer he spent in Woodstock, New York, a favored art community in the Hudson River valley. The composition recalls Auguste Renoir’s large portrait of Madame Charpentier and her children (1878), which had entered the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, to great acclaim in 1907. Bellows posed his wife, Emma, and their two daughters in an elaborately conceived arrangement that evokes bourgeois respectability. In contrast to the seemingly unruffled world of Renoir, the Bellows portrait betrays anxiety. Emma recalled the tension of their portrait sittings in a letter of 1943. Although Bellows’s portrayal of her and their younger daughter Jean went very well “from the start,” she noted that it was more difficult to incorporate their twelve-year-old daughter Anne. [1] With maternal protectiveness, Emma’s arm encircles Jean, who sits unabashedly with legs askew surrounded by billowing crinolines. In contrast, Anne, on the cusp of maturity, exhibits a distinct nervousness in the pose of her hands and a sense of adolescent self-consciousness in her stiffly crossed ankles.

In a 1923 letter to Robert Henri, Bellows described technical innovations he had developed that afforded him the same freedom while painting that he experienced in drawing. By laying out the composition in two colors at the outset, as seen in the purple and orange that dominate the study [63.261] for this portrait, Bellows achieved “the fresh first excitement” of the composition. [2] Seeking to emulate the spontaneity of Renoir and the French Impressionists and his teacher Henri, Bellows hoped to establish the essential idea of the composition in one day of painting.

Notes

1. Emma Bellows to Barbara N. Parker, May 28, 1943, curatorial files, Department of Art of the Americas, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

2. George Bellows to Robert Henri, November 1923, quoted in Michael Quick et al., The Paintings of George Bellows, exh. cat. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1992), 84.

This text was adapted from Elliot Bostwick Davis et al., American Painting [http://www.mfashop.com/9020398034.html], MFA Highlights (Boston: MFA Publications, 2003).

Provenance1923, the artist; 1925, by inheritance, Emma (Mrs. George) Bellows, N.Y.; 1925, the Boston Art Club; 1925, partial purchase and gift of the Boston Art Club to the MFA. (Accession Date: March 24, 1925)